Tags

COVID-19, Economic Recovery, Scotland, Scottish Government, strategic planning, Wellbeing Economy

Reflecting on the emergency measures introduced in March to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, the columnist Neal Ascherson observed, “The state is back.” And “the longer the virus emergency lasts,” he pointed out, “the more the memory of the pre-virus world begins to grow unreal, unconvincing. Now, unmistakably, there’s a feeling that ‘things will never be the same after it’s over’ and ‘we can’t go back to all that’.”

Reflecting on the emergency measures introduced in March to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, the columnist Neal Ascherson observed, “The state is back.” And “the longer the virus emergency lasts,” he pointed out, “the more the memory of the pre-virus world begins to grow unreal, unconvincing. Now, unmistakably, there’s a feeling that ‘things will never be the same after it’s over’ and ‘we can’t go back to all that’.”

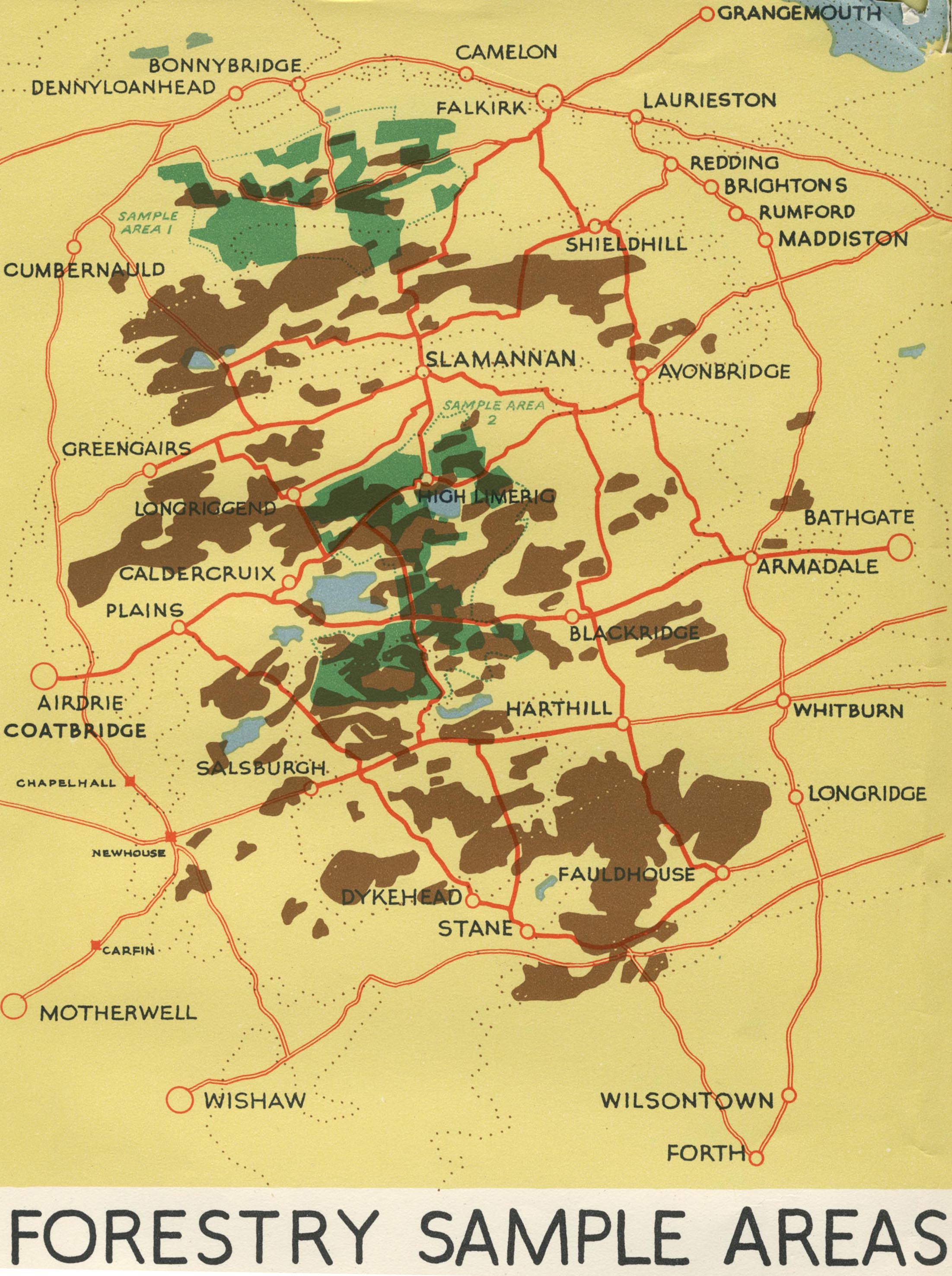

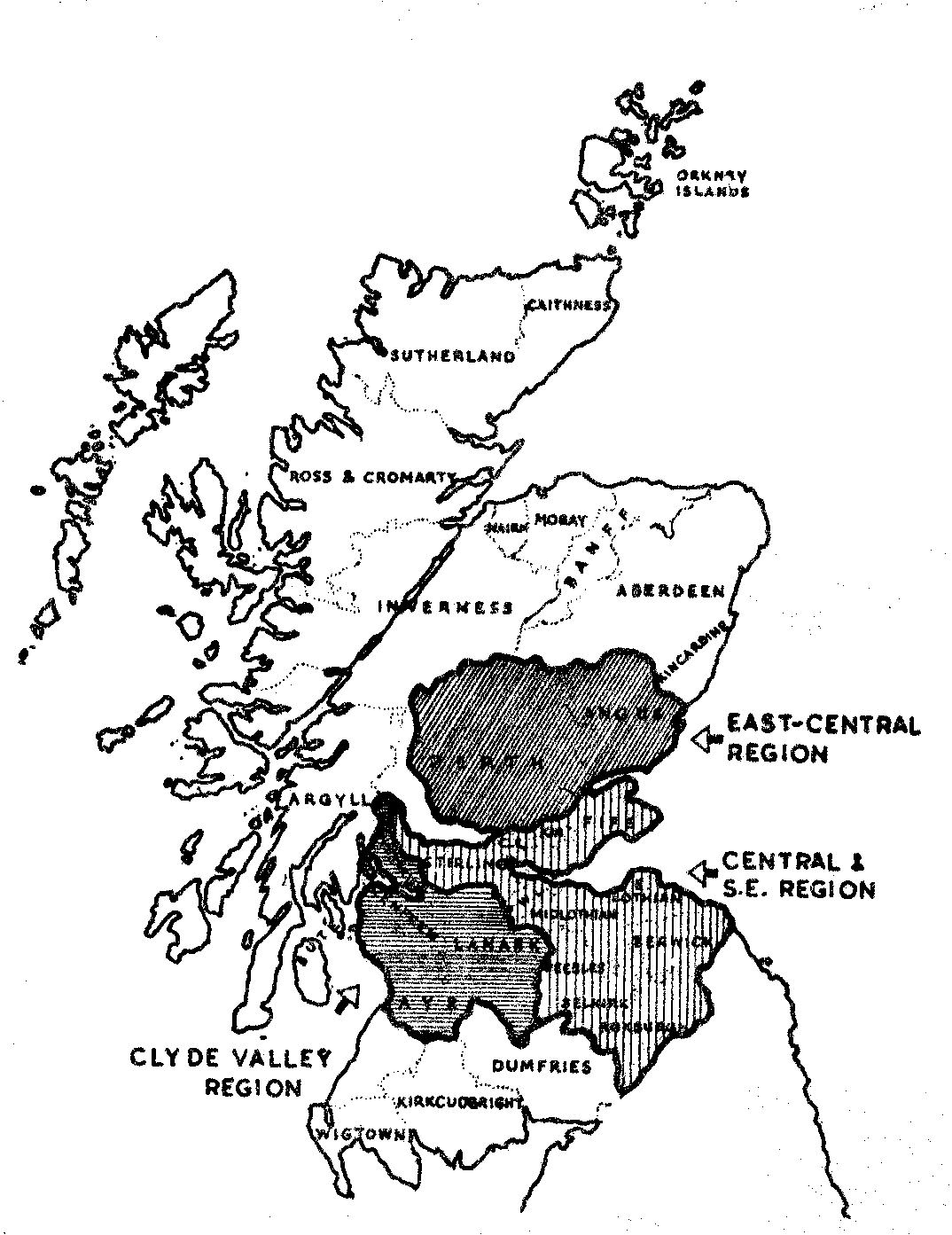

That feeling has arisen before. The trauma of the Great War led to the demand for ‘homes fit for heroes’ and the construction of good quality working class housing by local authorities right across Scotland, under the Housing and Town Planning (Scotland) Act of 1919. It arose again after the Great Depression. The ‘reconstruction planning’ which came to the fore after the Second World War was originally a response to Scotland’s experience of industrial depression and mass unemployment. Professor Douglas Robertson has drawn my attention to a film which captures the aspirations and vision of the time. Wealth of a Nation was one of seven documentaries made by Films of Scotland for the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow, under the supervision of John Grierson. It looks forward to better housing and social facilities, modern industrial estates, improved transport infrastructure, electrical power from the glens, and a National Park readily accessible to the population of West Central Scotland.

In April, the Scottish Government charged an independent advisory group chaired by Benny Higgins with providing expert advice on economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Their report, entitled Towards a Robust, Resilient Wellbeing Economy for Scotland, was submitted to the Scottish Government in June. On 5 August, the Scottish Government responded to the Advisory Group’s recommendations in a document entitled the Economic Recovery Implementation Plan.

Some of the recommendations in the Higgins Report are very much in tune with the thinking of the UK2070 Commission established under the chairmanship of Lord Kerslake to address regional inequalities across the United Kingdom. The Advisory Group calls for an investment-led recovery. It recognises the need to address regional disparities in Scotland and advocates a regionally focused model of economic development. However, unlike the Commission, it fails to make the necessary connections between economic development, strategic spatial planning and the strengthening of local government. Planning is portrayed as a regulatory impediment to recovery, part of the problem rather than an important part of the solution.

The Scottish Government’s Implementation Plan places emphasis on housing and infrastructure; decarbonising and greening the economy; economic and social renewal; and changing the way we work and travel. These are all areas where planners at national and local levels can contribute valuable skills and expertise. Regrettably, the Scottish Government neglects to recognise that fact.

Instead, the Implementation Plan follows the lead of the Advisory Group in seeing planning as a barrier to recovery. The Scottish Government’s commitments on Planning are ‘to carry out a comprehensive review of national planning policies and an extension of permitted development rights’; and an exploration of ‘the options to alleviate planning restraints.’ We are not told what these ‘restraints’ might be, but we can be fairly certain that bad developments in the wrong places will neither assist recovery nor contribute to wellbeing.

Neither reviewing national planning policy nor tinkering with permitted development rights will make any significant contribution to economic recovery. They will simply be a counter-productive distraction when the skills and energies of planners should be fully focused on measures to promote economic and social recovery.

Businesses large and small face huge challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Brexit will shortly deliver a further blow. It is entirely appropriate that measures to sustain and support them through and beyond the current crisis should be at the heart of the Scottish Government’s economic recovery plan. But the Higgins Report adheres to a discredited neoliberal narrative which seeks to portray the public sector as a barrier to rather than an essential partner in recovery. It seeks to set the public and private sectors in opposition to each other, when their roles are complementary. A successful recovery plan requires the building of a broad consensus on the way forward, not divisive rhetoric. The Scottish Government’s Council of Economic Advisers includes the former Chief Medical officer, Sir Harry Burns, who has long promoted the Wellbeing agenda, and Marianna Mazzucato, the champion of the entrepreneurial state. Katherine Trebeck is a leading advocate of the Wellbeing Economy based in Scotland. The Advisory Group on Economic Recovery would benefit from their wise counsel.

The Scottish Government’s Economic Recovery Implementation Plan indicates that the fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) will be brought to Parliament in September 2021. It also intends that the Regional Land Use Partnerships which will be introduced from 2021 should have a role in regional economic development and meeting climate change goals. The Scottish Government needs to develop a positive narrative which explicitly identifies Planning as an important agent of recovery, setting out the important contribution planners can make to delivering housing, creating better places, developing district and communal heating systems, economic and social renewal, improving infrastructure, and changing the way we work and travel; and explaining the roles the National Planning Framework and Regional Land Use Partnerships will play in providing a strategic spatial policy context for that work.

This article first appeared as a Built Environment Forum (BEFS) blog on 10 August 2020.